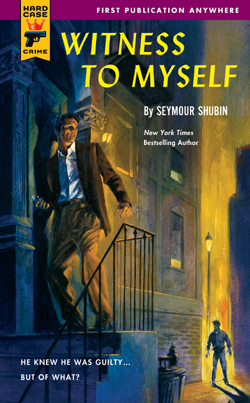

Seymour Shubin

Witness to Myself

Hard Case Crime, 2006

As a teenager Alan Benning once spends a holiday with his parents in a mobile home at the ocean. Alan runs along the beach, steps into the woods and about a mile away from where his parents left off meets a little girl. Her kite is stuck in a tree, and Alan helps remove the kite. Sexually excited, Alan attempts to touch the girl, she begs him not to hurt her, Alan panics and strangles her first, and then throws her on the ground.

Returning to his parents, Alan lays down with a fever, until the family is going away forever from the small town where the beach was located. From that moment fifteen years passes, Alan graduates from university, becomes a successful lawyer, gets a promising job in the charity-specialized company, dates a sweet and sympathetic nurse. But the episode at the beach, the outbreak of violence, does not make the hero rest. He should go back to this town and try to find out whether he had killed an innocent girl or not.

The novel with such dubious hero (an attack on a little girl does not honor him) is not told by Alan himself, but by someone close to him, his cousin Colin, working as a true-crime journalist. Colin writes articles for several tru-crime magazines, knows many detectives, watches popular TV shows about unsolved murders. And as the story is told by journalist, whom Alan have never talked about his only crime to, you can at the very beginning of the book conclude that Alan will pay for his act - and repent before his cousin.

Witness to Myself is a fine example of modern noir, quick, chilling, appealing for sympathy towards the main character, but which does not overdo it with the psychological stuff. Alan could easily come off the pages of an early novel written by Highsmith, only Shubin is not burdened with psychological layouts, trying to move faster with his story. Alan is of that category of noir heroes, whose near-perfect existence marred by a single shameful act from the past. And this act is sitting like cancer in his brain. Sooner or later, it will still kill its host. And it seems the more ideal he is for those who surround him, and in the course of the novel Alan really in everyone's eyes will be almost a saint, the harder he gets along with his past.

Shubin is a veteran writer and Witness to Myself indicates that the writer is still in excellent shape.